- Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky says the travel tech company lost 80% of its business in six weeks as the coronavirus pandemic crushed the travel industry.

- Chesky outlines how he guided Airbnb’s pandemic response with the company’s core principles, not profit motives.

- Travel spending is returning, according to Airbnb, but to smaller cities and less crowded destinations.

Airbnb CEO and co-founder Brian Chesky was close to taking the travel tech company public in March, ready to expand into areas as far-flung as booking flights and publishing. Then, the coronavirus hit — first in China, where Airbnb does plenty of business, and then around the world.

Within six weeks, Airbnb lost 80% of its business linking travelers to homeowners offering places to stay. “It’s like slamming the brakes on a car while you’re going 100 miles an hour,” Chesky said in a Reuters Newsmaker webinar last week. “It’s going to be really rough.”

“We got more than a billion dollars of cancellations from guests,” he added, “We knew this was basically a once-in-a-century event and that decades from now — if we’re lucky enough to be around in decades — we’d have indelible marks from the decisions made over the course of weeks.”

Chesky said he decided Airbnb’s next moves would be guided by principles, not profits, in hopes it would help the company in the long run — a core belief advocated by impact investors and others asking companies to follow environmental, social and governance guidelines.

“I think a business decision you make assumes the best outcome for the company,” he explained. “A principled decision is: ‘The world is so crazy, I don’t even know what’s going to happen. How will I be remembered?’ I want to be remembered for doing what I thought was the right thing.”

Airbnb decided to issue more than $1 billion in refunds to guests who could not travel because of the pandemic, a move that did not sit well with hosts counting on the money from those bookings. The company then gave $250 million of its own money to the hosts to help cushion the blow.

“Even before the pandemic, $250 million is meaningful for any company,” Chesky said. “But in a pandemic, where you’re hemorrhaging cash and you don’t even know if you can raise more money — and that was the circumstance for us in March — this was a meaningful amount of money for us, very meaningful.”

Next, came the layoffs — 1,900 people, about 25% of its employees. “We couldn’t afford to keep everyone,” Chesky said. “We said, ‘We don’t know when travel is gonna recover and, when travel does recover, it’s going to look totally different.’ So we had to focus our business.”

Airbnb has always touted itself as a company built on connection, between its customers and hosts, and between its workers, who many said felt like a family. However, the company was forced with the decision of saying goodbye to members of the family or worrying that the whole enterprise may not survive.

It’s a struggle that many “commitment culture” companies face, especially in financially turbulent times like now because part of the compensation was being part of a family, Ethan Mollick, an entrepreneurship professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, told the New York Times.

“Now the family goes away, and the deal is sort of changed,” Mollick said. “It just becomes a job.”

When Chesky announced the layoff online and in a letter to employees, he offered his displaced workers 14 weeks of severance, a year of health insurance and access to outplacement services. “I am truly sorry,” he told them. “Please know this is not your fault. The world will never stop seeking the qualities and talents that you brought to Airbnb.”

Forbes said the layoff plan was a “master class in empathy and compassion.” Inc. called it a “gut-wrenching, yet powerful lesson in leadership and communication.” The entrepreneur magazine Grey turned it into a template for “the right way” to layoff employees.

Some workers complained — anonymously because they had signed non-disparagement agreements — that they felt betrayed when they were let go, especially after Airbnb subsequently raised $2 billion in financing. Some contractors complained that their severance was not handled nearly as well. “This glowing coverage failed to reckon with the full picture of layoffs, which includes an invisible workforce of contractors locked out from accessing those benefits,” former Airbnb contractor Anna Furman wrote in Wired, adding that longtime contractors received only one week of severance.

“We did raise $2 billion,” Chesky explained to Reuters. “But it was a loan. It was debt. It wasn’t equity because the markets were so volatile and we were basically entering somewhere between a recession and a depression… Investors weren’t really interested in trying to value a travel company.”

At some point, though, investors will be placing a price on Airbnb, which still plans to go public and believes its unique business model is still attractive, especially as people begin to travel again.

“Most people don’t want to get on airplanes, but they are willing to get in a car and they’re willing to drive somewhere,” Chesky said. “They’re not really interested in going to big cities. They want to go to less urban areas — small towns, rural areas, even national parks.”

Chesky declined to talk about how Airbnb would go public, whether it would be through an IPO, direct listing or even through a now-trendy special-purpose acquisition company also known as a SPAC or a blank-check company. Though he acknowledged the recovering IPO market, he said none of the recent successes came from the travel sector.

“I think investors are going to like a lot of things we’re doing,” he said. “There’s going to be some things that they don’t like.”

Airbnb’s numerous stakeholders, including governmental entities as well as business partners and customers, complicates their business. “Unlike other companies, we don’t just make a widget,” Chesky said. “Whatever pressure I feel as a public company CEO — and it will be great — it will never, ever, probably compared to the kind of pressure I felt having a business drop 80% in six weeks or so…”

“We know investors are watching and we’re still going to act with our principles. And frankly, great investors are going to like that.”

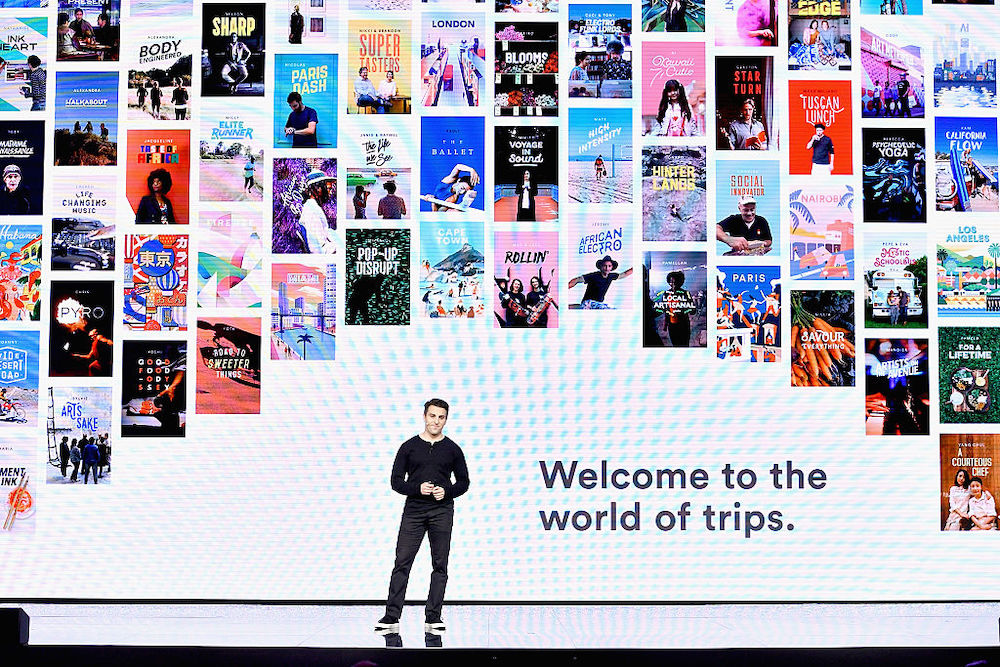

Photo by Mike Windle/Getty Images for Airbnb