- Want to change a company’s behavior? Prepare to spend as much as a year getting your proposal in order.

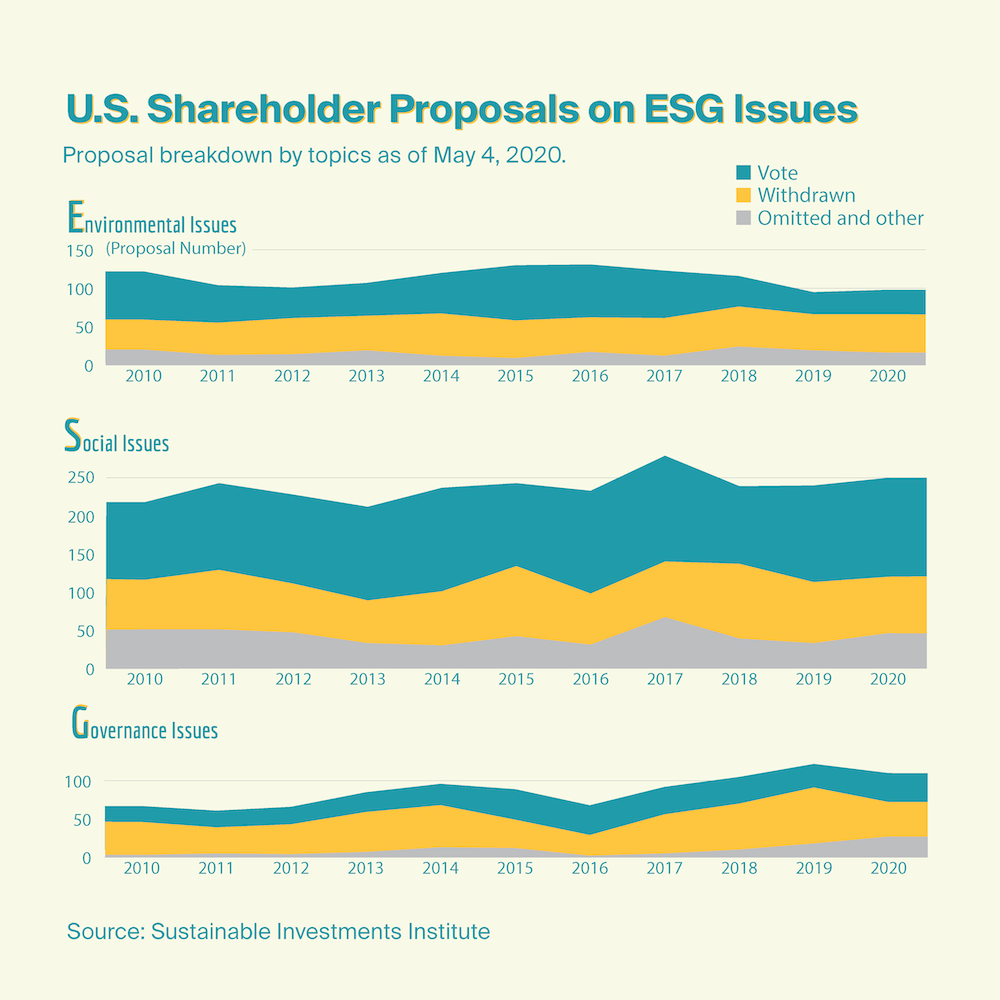

- More shareholders are filing proposals, apparently undeterred by the task’s complexity.

- U.S. and EU systems vary, with experts seeing complexity in the U.S. exacerbated by multiple jurisdictions.

Using a shareholder resolution to force a public company to change its business practices isn’t easy, especially in the United States.

Still, the rising number of shareholder resolutions shows it’s possible.

The process in the U.S. is complicated by multiple state jurisdictions with varying legal frameworks that govern the process, says Vadim Avdeychik, a lawyer at the investment management practice of Paul Hastings.

Intrepid investors determined to have their voices heard must be ready to put in time and give themselves up to a year to prepare their resolution, experts say.

First, they need to check the laws in the state where a company is incorporated and review company bylaws or articles of incorporation for how, when and where to submit their proposals. Public companies file their bylaws with the SEC and documents can be retrieved from the online EDGAR system. Otherwise, investors can request the bylaws from the company.

Once an investor files a petition, companies can exclude it from being voted on at annual meetings for failing to meet specific criteria. Companies typically notify investors in writing if their petitions have been rejected. Sometimes, companies ask the SEC to allow them to exclude proposals. The agency can then issue a no-action letter in favor of the company or agree with the shareholder and enable the proposal to move forward.

The SEC says it will no longer issue such letters due to the volume of petitions it has received in the past years.

[ Read: Karma’s deep dive on investors pushing ESG values into boardrooms ]

Aggrieved shareholders who wish to contest rejected proposals can file a lawsuit against the company. Experts say such a move could run out the clock on the deadline for the submission process.

But last year, Saba Capital Management, a hedge fund with $1.7 billion in assets under administration, sued two BlackRock closed-end funds after the funds tried to exclude its proposal to nominate new board members to the two entities. A Delaware-based court ruled in favor of the hedge fund, saying the proposal should be put to a vote at an annual meeting.

In Europe, the process is less contentious.

European companies can also exclude resolutions on technicalities, but have seldom done so to date. The higher threshold requirements for filing a resolution in countries such as the U.K. mean that proposals are less common — and usually require a higher degree of support among shareholders from the start.

Activist investors in the U.K. need the support of 100 individual shareholders holding shares with an aggregate nominal value of £10,000 or 5% of all eligible shareholders to be able to file a resolution at an annual general meeting.

Companies that block resolutions can become fodder for unflattering media coverage. The fear of bad publicity acts as a deterrent to standing in the way of proposals, say activists.

Still, companies headquartered in Europe challenge investor-led proposals in different ways.

When ShareAction, a nonprofit that works with activist investors, spearheaded a resolution this year asking Barclays to phase out financing for fossil-fuel companies that are not aligned with the goals of the Paris Climate Accord, the U.K.-based bank responded by filing its own resolution which had the support of the board and eventually got a majority of the shareholders’ votes.

Barclays’ resolution committed the bank to becoming a net-zero emissions financing institution by 2050, but did not say the company would phase out its support for non-Paris compliant companies, says Jeanne Martin, a senior manager for banking standards at the nonprofit. Despite the challenges, the shareholder action was a success, she says.

“If a company doesn’t support your resolution, that doesn’t matter because we found resolutions … often kickstart a big debate about for example the company’s role [in tackling] climate change,” Martin told Karma. “So we see value in both resolutions that pass and resolutions that change the conversation.”